The longest spaceflight up to that time ended on Feb. 8, 1974, when Skylab 4 astronauts Gerald P. Carr, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue splashed down in the Pacific Ocean after their 84-day mission aboard Skylab, America’s first space station. During their stay, they carried out a challenging research program, including biomedical investigations on the effects of long-duration space flight on the human body, Earth observations using the Earth Resources Experiment Package, and solar observations with instruments mounted in the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). To study newly discovered Comet Kohoutek, scientists added cometary observations to the crew’s already busy schedule, including adding a far ultraviolet camera to Skylab’s instrument suite. The astronauts conducted four spacewalks, a then-record for a single Earth orbital mission.

Left: View from the Skylab 4 Command and Service Module (CSM) shortly after undocking from Skylab. Middle: Skylab during the final fly around, with the CSM’s shadow visible on the solar array. Right: Distant view of Skylab as the crew departed.

Carr, Gibson, and Pogue spent the first week of February 1974 finishing up their experiments, preparing the station for uncrewed operations, and packing their Command Module (CM) with science samples and other items for return to Earth. On Feb. 8, they closed all the hatches to Skylab and undocked their CM. Carr flew a complete loop around Skylab, the crew inspecting the station, noting the discoloration caused by solar irradiation. The sunshade installed by the Skylab 3 crew appeared to be in good condition. Finally, Carr fired the spacecraft’s thrusters to separate from the station. Three and a half hours after undocking, they received the go for the deorbit burn and fired the Service Module’s (SM) main engine. After 84 days in weightlessness, the burn felt like “a kick in the pants” to the astronauts. They separated the CM from the SM, but when Carr tried to reorient it with its heat shield forward for reentry, nothing happened! Carr switched to a backup system and corrected the problem, caused by an inadvertent flipping of the wrong circuit breakers. Reentry took place without incident, the two drogue parachutes opened at 24,000 feet to slow and stabilize the spacecraft, followed by the three main parachutes at 10,000 feet to slow the descent until splashdown.

Left: Splashdown of Skylab 4, ending the longest crewed mission to that time. Right: The Skylab 4 Command Module in the apex down or Stable II position.

Splashdown of Skylab 4 took place 176 miles from San Diego and three miles from the prime recovery ship the helicopter carrier U.S.S. New Orleans (LPH-11). The mission of 84 days 1 hour 16 minutes set a human spaceflight duration record for that time. Carr, Gibson, and Pogue had orbited the Earth 1,214 times and traveled 70.5 million miles. The CM first assumed a Stable II or apex down orientation in the water. Balloons at the top of the spacecraft inflated within minutes to right it to the Stable I or apex up position. In Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, flight controllers met the splashdown with mixed feelings – elation at the conclusion of the longest and highly successful mission and sadness at the end of the Skylab program with an upcoming prolonged hiatus in human spaceflights until the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975. The three major television networks chose not to carry the splashdown live, the first American splashdown not covered live since the capability began with the Gemini VI mission in 1965. The networks deemed the event not newsworthy.

Mission Control at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston shortly after the Skylab 4 splashdown.

Left: Recovery helicopter from the U.S.S. New Orleans about to drop swimmers into the water. Middle: Swimmers attach an inflatable collar around the Skylab 4 Command Module (CM). Right: Sailors lift the CM onto an elevator deck on the New Orleans.

Within 40 minutes of splashdown, recovery teams had placed an inflatable collar around the spacecraft and lifted it aboard the New Orleans. Seven minutes later, they had the hatch open and flight surgeons quickly examined the three astronauts, declaring them to be healthy.

Left: Aboard the U.S.S. New Orleans, Edward G. Gibson emerges first from the Skylab 4 Command Module (CM). Middle: William R. Pogue stands after emerging from the CM. Right: Skylab 4 crew members Gibson, left, Pogue, and Gerald P. Carr seated on a forklift platform after emerging from the CM and on their way to the medical facility.

Gibson, riding in the spacecraft’s center seat, emerged first, followed by Pogue. Carr exited last, befitting his role as commander. They walked the few steps to a platform where they could sit and wave to the cheering sailors. A forklift picked up the entire platform with the astronauts, and transported them to the Skylab mobile medical facilities aboard the carrier. Extensive medical examinations of the astronauts continued throughout landing day while the carrier sailed toward San Diego.

Left: Skylab 4 Commander Gerald P. Carr enjoys a cup of coffee during medical testing aboard the U.S.S. New Orleans. Right: During a break from medial testing, the Skylab 4 astronauts mingle with some of the crew aboard the New Orleans.

Medical exams revealed Carr, Gibson, and Pogue to have withstood the rigors of weightlessness better than the previous two Skylab crews despite having spent more time in space. They attributed this to their increased exercise regimen, including the use of the Thornton treadmill, and better nutrition, an assertion backed up by flight surgeons and scientists. While on board ship, they had limited contact with the staff, all of whom wore protective masks when in close proximity to the crew to maintain the strict postflight medical quarantine.

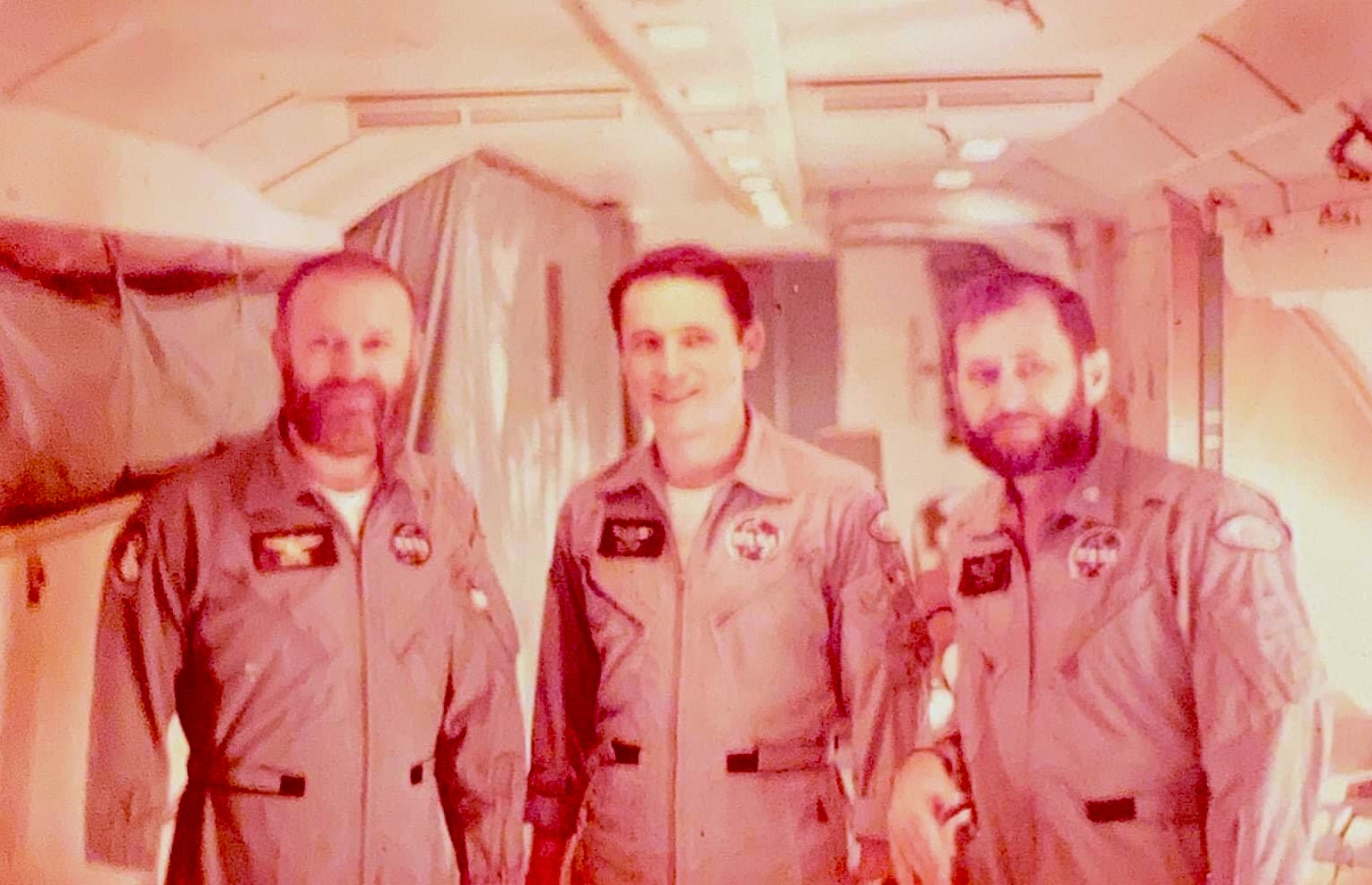

Left: From aboard the U.S.S. New Orleans, Skylab 4 astronauts Gerald P. Carr, left, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue wave to the crowd assembled dockside at North Island Naval Air Station (NAS) in San Diego. Middle: Carr, top, Gibson, and Pogue board a U.S. Air Force transport jet at North Island NAS that flew them to Houston. Right: Carr, Gibson, and Pogue aboard the transport jet on their way to Houston.

Carr, Gibson, and Pogue remained aboard the New Orleans until completion of the landing plus 2-day medical exams. The ship had arrived at North Island Naval Air Station in San Diego the morning of Feb. 9, and the astronauts participated in a dockside welcoming ceremony while remaining on the carrier. The next day, the trio left the carrier and boarded a U.S. Air Force transport jet that flew them to Ellington Air Force Base in Houston.

Left: At Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, Skylab 4 astronauts Gerald P. Carr, bottom, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue descend the steps from the U.S. Air Force jet that had flown them from San Diego. Middle: Pogue, left, Gibson, and Carr hug their wives for the first time in more than three months. Right: On the podium at Ellington, Carr, left, Gibson, and Pogue address the welcoming crowd.

Upon deplaning at Ellington, Carr, Gibson, and Pogue reunited with their wives, JoAnn, Julia, and Helen, respectively, whom they had not seen in three months. Director of JSC Christopher C. Kraft introduced them to the several hundred well-wishers who turned out to welcome the astronauts back to Houston.

Left: Gerald P. Carr, left, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue address reporters at their postflight press conference on Feb. 22. Middle: President Richard M. Nixon speaks to the assembled crowd at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston during the ceremony where he presented the Skylab 4 astronauts, sitting on the podium with their wives, with the Distinguished Service Medal on March 20, 1974. Right: In April 1974, the Skylab 4 astronauts address the assembled employees in the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The astronauts soon returned to work at JSC for a series of debriefings about their mission. During a press conference on Feb. 22, they showed a film of their experiences aboard Skylab and answered reporters’ questions. During a visit to Texas, on March 20, President Richard M. Nixon stopped at JSC to award Carr, Gibson, and Pogue the Distinguished Service Medal in a ceremony attended by thousands of employees and visitors.

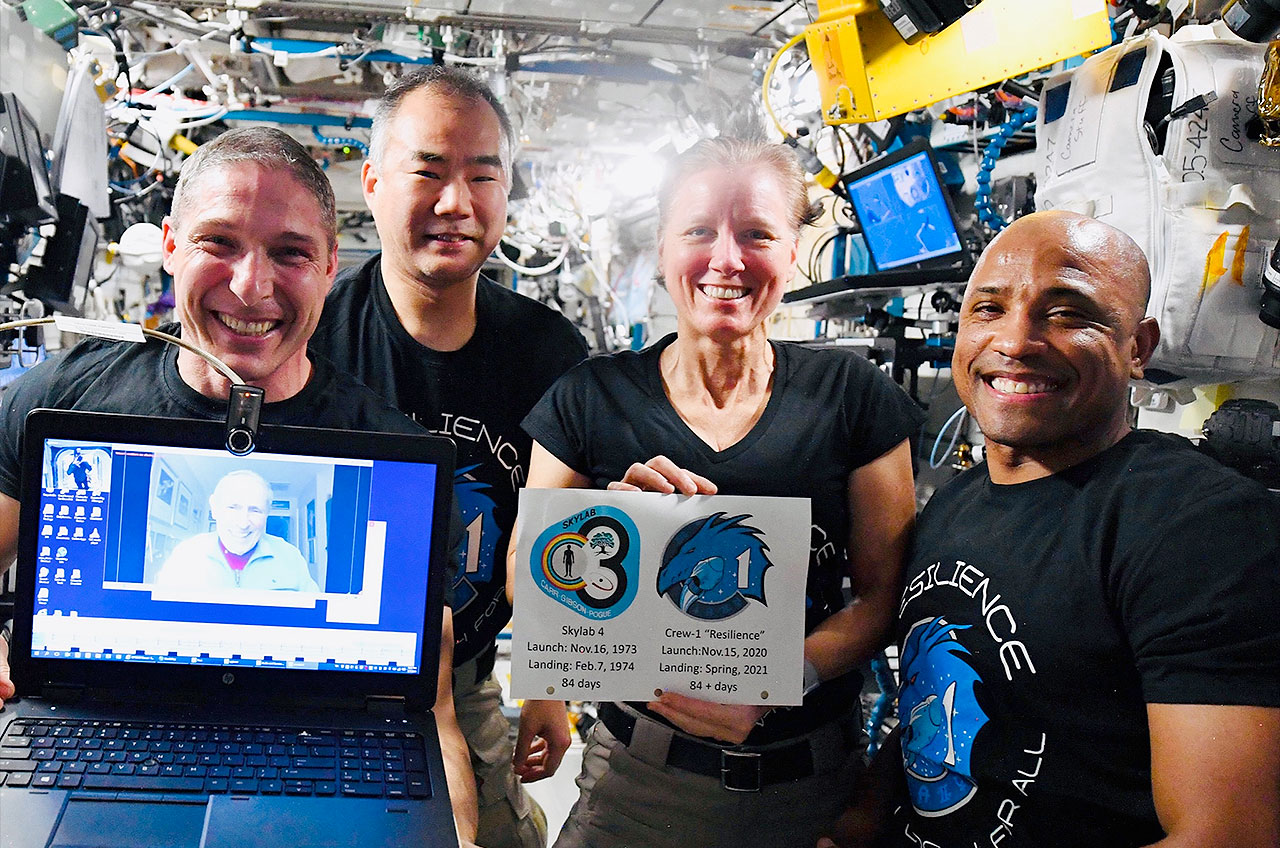

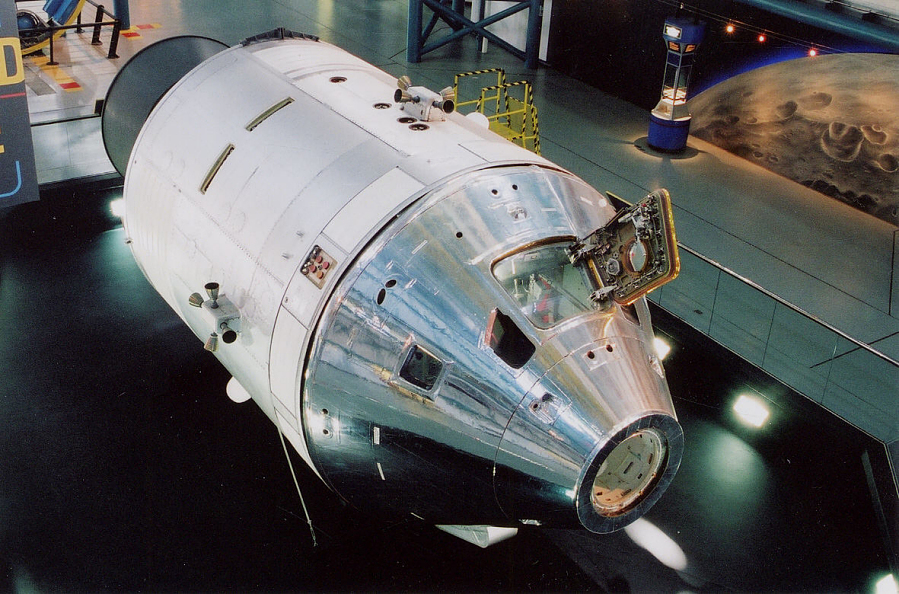

Left: The Skylab 4 Command Module on display at the Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City. Image credit: courtesy Oklahoma History Center. Right: The Crew-1 astronauts aboard the space station talk with Skylab-4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson.

Following splashdown, the U.S.S. New Orleans delivered the CM to San Diego, from where workers trucked it to its manufacturer, the Rockwell International facility in Downey, California, for postflight inspection. NASA transferred the Skylab 4 CM to the National Air and Space Museum in 1975, where it went on display the following year when the Smithsonian Institution inaugurated its new building. After more than 40 years (1976 to 2018) on display there, in 2020, the NASM loaned the spacecraft to the Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City. The Skylab 4 CM held the record for the longest single flight for an American spacecraft for 47 years until Feb. 7, 2021, when the Crew Dragon Resilience flying the SpaceX Crew-1 mission to the International Space Station broke it. To commemorate the event, the four-person crew of Crew-1 held a video conference with Gibson from the space station.

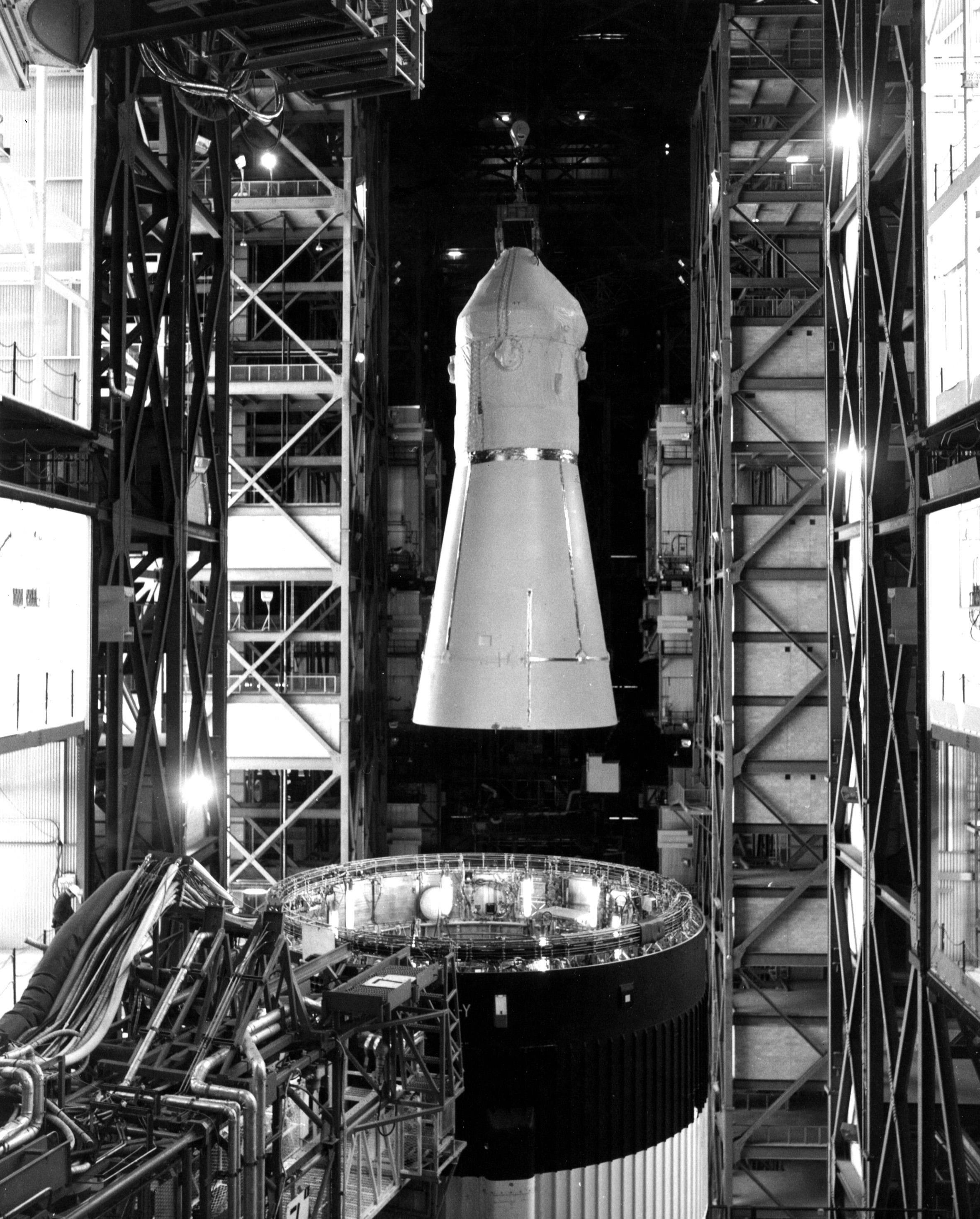

Left: The Skylab 4 rescue vehicle returns to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida on Feb. 14, 1974. Middle: Workers in the VAB destack the Skylab rescue spacecraft Command and Service Module-119 (CSM-119) from the SA-209 Saturn IB rocket. Right: The Skylab 4 CSM-119 rescue spacecraft on display in the KSC Apollo/Saturn V Center.

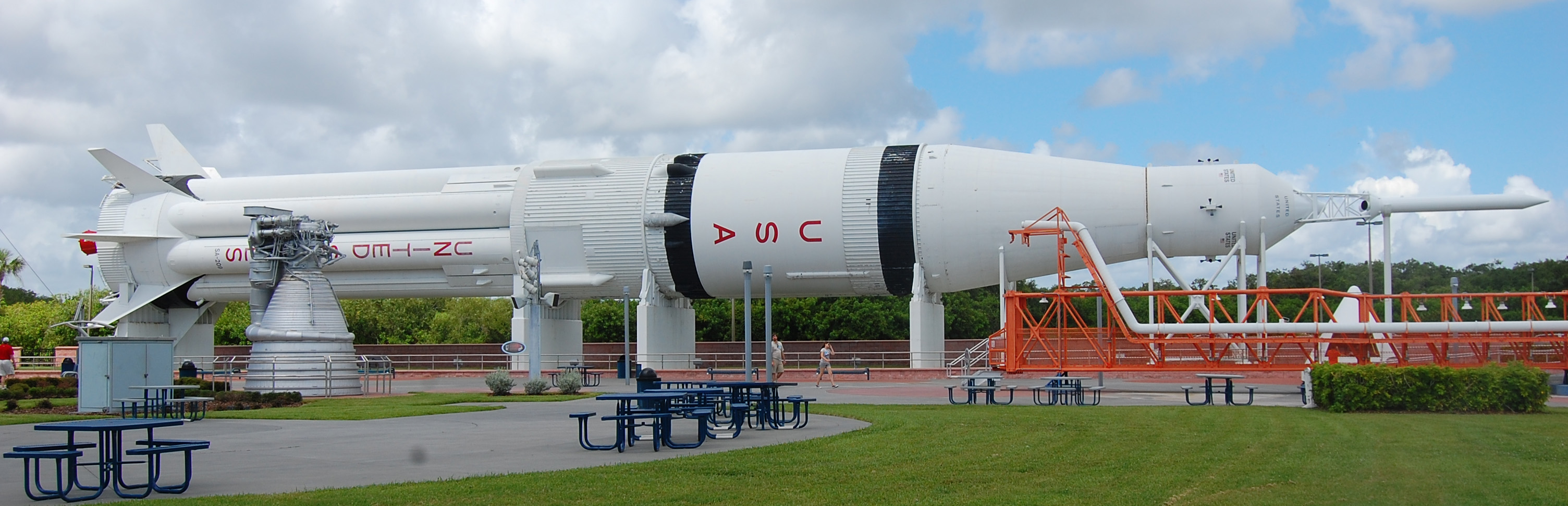

The Skylab 4 SA-209 Saturn IB rocket on display at the Visitor Center’s Rocket Garden at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The rocket is topped with the Facility Verification Vehicle Apollo Command and Service Module.

The Skylab Rescue Vehicle’s rocket (SA-209) and spacecraft (CSM-119), on Launch Pad 39B since Dec. 3, 1973, returned to the Vehicle Assembly Building on Feb. 14, 1974. Workers destacked the vehicle, keeping the components in storage at KSC. Managers designated SA-209 and CSM-119 as the backup vehicle for the July 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Engineers used the spacecraft to conduct lightning sensitivity testing in KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building’s high bay in September 1974. Following ASTP, NASA retired both the rocket and spacecraft, eventually putting them on display. Visitors can view the SA-209 Saturn IB in the Rocket Garden of KSC’s Visitor Center and the CSM-119 in the Apollo/Saturn V Center at KSC.

Left: Illustration of a possible Skylab reboost mission by a space shuttle. Middle: Track of Skylab’s reentry over Australia. Right: Managers, flight directors, and astronauts monitor Skylab’s reentry from Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Two days before leaving Skylab, the Skylab 4 crew boosted the station into a higher 269-by-283-mile orbit, assuming it would remain in space until 1983. By then, NASA hoped that space shuttle astronauts could attach a rocket to the station to either boost it to a higher orbit or safely deorbit it over the Pacific Ocean. But delays in the shuttle program and higher than expected solar activity resulting in increased atmospheric drag on the station ultimately thwarted those plans. It became apparent that Skylab would reenter in mid-1979, forcing NASA to devise plans to control its entry point as much as possible by adjusting the station’s attitude to influence atmospheric drag. On July 11, 1979, during its 34,981st orbit around the Earth, engineers in JSC’s Mission Control sent the final command to Skylab to turn off its control moment gyros, sending it into a slow tumble in an effort to ensure that Skylab would not reenter over a populated area. Skylab’s breakup resulted in most of the debris that survived reentry falling into the Indian Ocean, with some pieces falling over sparsely populated areas of southern Western Australia.

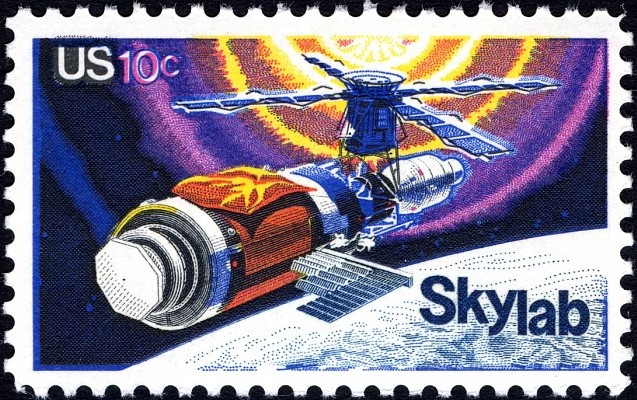

Left: The Skylab postage stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Service. Image credit: courtesy Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Right: Skylab 2 Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, center, accepts the Collier Trophy from Vice President Gerald R. Ford, right, as Skylab 4 Commander Gerald P. Carr, left, and Skylab 3 Commander Alan L. Bean look on.

The scientific results returned during the 171 days of human occupancy aboard Skylab remain some of the most significant in the history of spaceflight. The medical studies on the astronauts represent the first comprehensive look at the human body’s response to long-duration spaceflight. The ATM solar telescopes took more than 170,000 images for astronomers, while Earth scientists received 46,000 photographs. The Skylab program received many accolades. The U.S. Postal Service honored it by releasing a stamp in the program’s honor on May 14, 1974, the 1-year anniversary of Skylab’s launch. The National Aviation Association awarded its prestigious Robert J. Collier Trophy to the nine Skylab astronauts and to Skylab Program Director William C. Schneider for “proving beyond question the value of man in future explorations of space and the production of data of benefit to all the people on Earth.” Vice President Gerald R. Ford presented the award on June 4, 1974.

Left: The Skylab backup flight unit on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Image credit: courtesy NASM. Right: The Skylab trainer on display at Space Center Houston.

Possible plans for launching the Skylab backup flight unit never materialized due to budget constraints. That unit is on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The training units of the various Skylab modules are on display at Space Center Houston, JSC’s official visitors center.

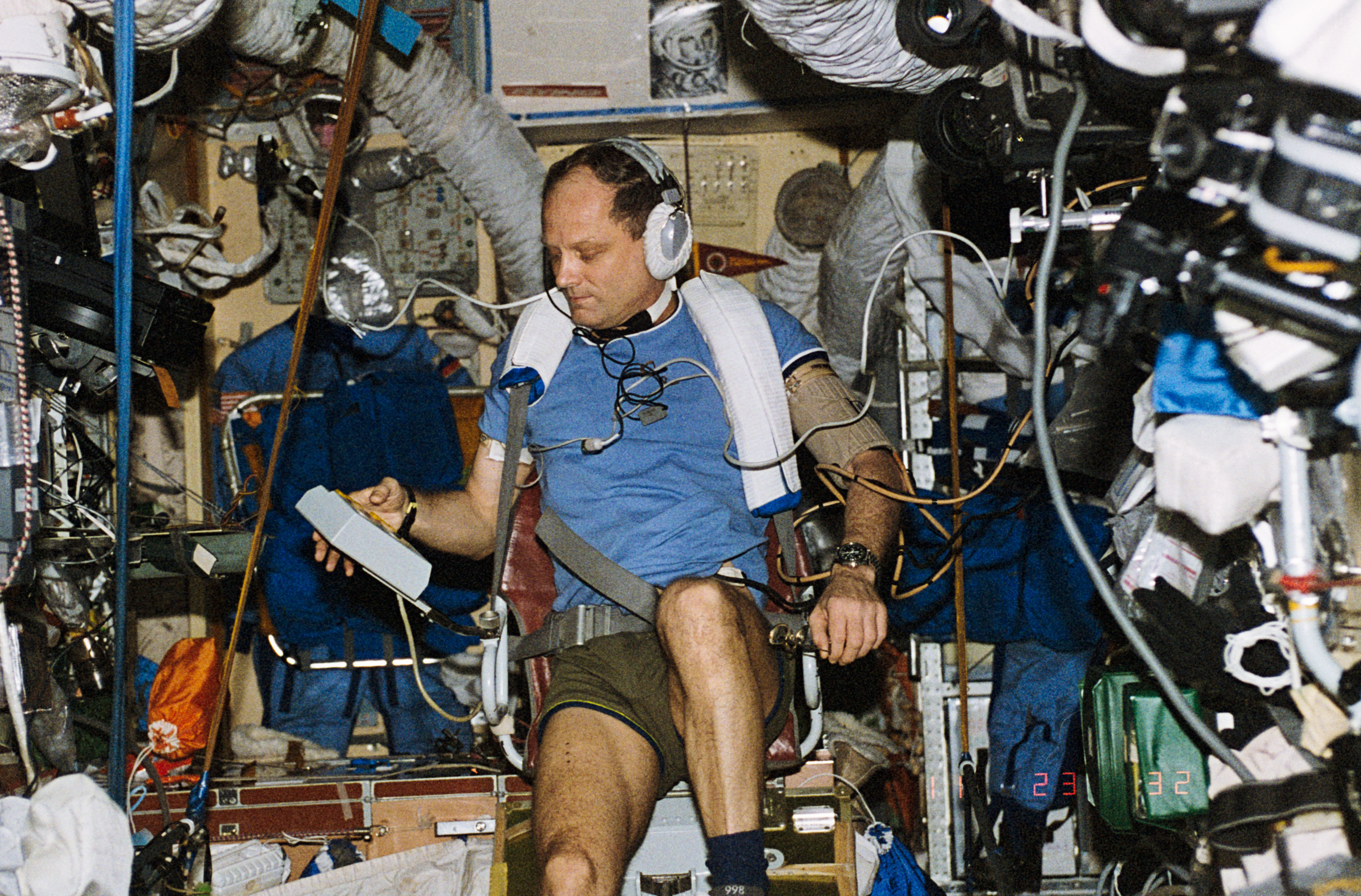

Left: Soviet cosmonauts Georgi M. Grechko, left, and Yuri V. Romanenko during their record-breaking 96-day mission aboard Salyut 6. Right: NASA astronaut Norman E. Thagard during his American record-breaking 115-day flight aboard Mir.

As for the record for longest spaceflight, Skylab 4’s 84-day mark held for four years, when Soviet cosmonauts Yuri V. Romanenko and Georgi M. Grechko surpassed it, spending 96 days aboard the Salyut 6 space station from December 1977 to March 1978. As an American record it held up longer, broken by NASA astronaut Norman E. Thagard during his 115-day flight aboard the Russian space station Mir between March and July 1995. Operational lessons learned from Skylab proved invaluable for the Shuttle-Mir and International Space Station programs.

For more insight into the Skylab 4 mission, read Carr’s, Gibson’s, and Pogue’s oral histories with the JSC History Office.

With special thanks to Ed Hengeveld for his expert contributions on Skylab imagery.

from NASA https://ift.tt/lE1Ovjx